Bruce is a retired Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Leeds. In September 2020, he suffered a stroke. Five years on, he is now an active member of the West Yorkshire Integrated Stroke Delivery Network (ISDN) Life After Stroke (LAS) Co-production Group, which consists of stroke survivors, carers, voluntary and community organisation representatives, and NHS professionals, working together to improve experiences and outcomes for people following a stroke.

Bruce is a retired Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Leeds. In September 2020, he suffered a stroke. Five years on, he is now an active member of the West Yorkshire Integrated Stroke Delivery Network (ISDN) Life After Stroke (LAS) Co-production Group, which consists of stroke survivors, carers, voluntary and community organisation representatives, and NHS professionals, working together to improve experiences and outcomes for people following a stroke.

Bruce has documented his experience – from his initial stroke, his treatment, through to his recovery. In a series of three blogs, we will share Bruce’s experience, with the hope that it inspires fellow stroke survivors on their journey to recovery.

Part three: Life after stroke

Life will be different

When I first came home from hospital, I was able to function through the day but there were a number of basic things that I couldn’t do, even tying shoelaces (later, I discovered elastic laces!). On top of needing support, I was just not able to do the sort of household tasks that I used to contribute to. While I had an optimistic hope that I would soon be independent again, my wife was fearful that she would be tied forever into a major role as my carer. To start with I could do very little of any value, and what I could do took me so long that it was always easier for my wife to do it instead. Unfortunately, that wouldn’t help my physical recovery and wouldn’t give me the satisfaction of being useful - a great boost for my mental wellbeing. We realised that she had to leave me alone to get on with some things, because that was essential therapy, but I had to make sure I kept out of her way if she had things to do – I’m still learning about that.

About five months after I came home from hospital, my wife was diagnosed with breast cancer. Suddenly we had a whole new concern, and my stroke was no longer the critical issue. Over the following months, as she had to deal with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy it was inevitable that I would have to raise my game to help out. Our children don’t live locally but still came home to help at the most difficult times, but we also got help from friends in many ways. While my wife couldn’t drive, a group of friends who I meet for beer and curry every month volunteered to take me to physiotherapy. They were retired and were happy to help us out once I took the plunge and asked. Fortunately, she has recovered well but my initial pattern of dependency was broken. After she had recovered, she was able to go off and leave me alone for a few days’ recuperation.

Getting Mobile

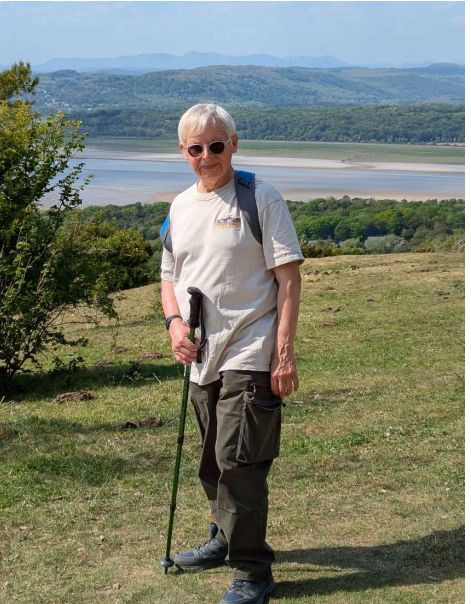

Learning to walk again is an ongoing saga with no end in sight, but I can walk further and faster every year and am now up for country walks and modest climbs. At first, I used an elastic foot-up strap and walked with a quad stick. The 100 yards to the end of the road was a major journey, undertaken at glacial speed, and the first few times my wife accompanied me with a wheelchair. Progress was very slow, but my walking was improving. Soon, I abandoned the quad stick for a regular walking pole which I keep set long to help maintain good posture. After nine months, I could get to our nearest café which was a great morale boost.

The biggest change happened after Jill referred me to the gait clinic at Chapel Allerton Hospital, and I was issued with a functional electrical stimulation (FES) unit. This piece of equipment sends an electrical signal to lift my right foot as I step and has made an enormous difference. I can now cross the road fast enough to avoid getting run over! My walking has continued to improve even after using it for three and a half years, and this year for the first time I am managing a two mile round trip for coffee in Roundhay Park, Leeds.

For trips out or for city shopping I have also found electric wheelchairs a tremendous help. Many country houses, gardens and castles have them available for a nominal hire charge, while Shopmobility provide them in many city centres. I have not bought my own because I can get everywhere by walking or driving, and I did not want to be tempted to take a wheelchair when I could walk.

When Jill first suggested that I might be able to drive a modified car, despite being unable to use my right limbs, I was very surprised. But she pointed me to the William Merritt Disabled Living Centre and after the inevitable delays due to Covid, I was able to have a try-out in a modified car. This went as well as could be expected, given the difficulty in braking smoothly with your left foot. I took a series of lessons but, despite favourable reports, the DVLA were less easily convinced that I would be safe behind the wheel, and I had to be appraised by an examiner at a driving test centre before they would issue a new licence. I also got a modified automatic car of my own. As with so much of stroke recovery, it helps if you have some money put by. At first, I found driving with a hand control (“lollipop”) on the steering wheel was quite tiring, but I have gradually got used to it and can manage for up to about two hours; any longer and my wife and I share the driving, with it just taking seconds to switch the car over for a normal driver.

Final thoughts

It would be silly to suggest that having a stroke has not changed my life massively. Many of the things I had planned for my retirement are no longer feasible, but there are a lot of things that I can still enjoy. One of the biggest differences however is that now everything takes much longer than it used to. I also spend a significant amount of time each week on physiotherapy. Physical activity is much harder than before my stroke, but I am beginning to enjoy country walks again. I had thought I would be able to return to long-forgotten hobbies such as model-building, but so far, my manual dexterity is not good enough, but it’s improving. Anything that can be done seated at a computer is reasonably straightforward, but I try to get up and moving as much as possible.

At the same time, there has been a big impact on my wife and carer. Fortunately, I am independent enough that she can do many of the things she used to, but we both miss things we used to do together. She continues with many of her existing activities, but I am very conscious that there are times I should be supporting her but can’t, and she is carrying a heavier burden than I would wish.

To get through a stroke and come out with a reasonably independent and enjoyable life needs patience and persistence above all else, plus good support to smooth the path to recovery and get through the basics of life. Stroke recovery is a long process, and my experience so far is that if you keep working at it you will keep improving. The other essential is to have as much good physiotherapy as you can get. My initial instincts were to do whatever it took to achieve a short term physical objective, even if it used the wrong muscles and hindered long term recovery. Eventually I got the message that doing it right is what matters most. In addition to NHS and paid-for private physiotherapy, I have managed to spend several days as a volunteer on courses for physiotherapists dealing with strokes, which has been a great experience. In all of this, it really makes a difference to manage to have some good times with friends and family. It may seem like a lot of effort, but every time I get out to do things and meet people, it proves to be well worth while. There have been many times when I wished I had known earlier about particular aids to coping and recovering. I am delighted that resources like the All Things Stroke website now exist, which carers and family members, as well as stroke survivors ourselves, can turn to for support groups and advice.

Sailing at Brough, May 2023.

Sailing at Brough, May 2023.

Canoeing on the Norfolk Broads, July 2024. Looks like I wasn't pulling my weight!

Canoeing on the Norfolk Broads, July 2024. Looks like I wasn't pulling my weight!