Bruce is a retired Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Leeds. In September 2020, he suffered a stroke. Five years on, he is now an active member of the West Yorkshire Integrated Stroke Delivery Network (ISDN) Life After Stroke (LAS) Co-production Group, which consists of stroke survivors, carers, voluntary and community organisation representatives, and NHS professionals, working together to improve experiences and outcomes for people following a stroke.

Bruce is a retired Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Leeds. In September 2020, he suffered a stroke. Five years on, he is now an active member of the West Yorkshire Integrated Stroke Delivery Network (ISDN) Life After Stroke (LAS) Co-production Group, which consists of stroke survivors, carers, voluntary and community organisation representatives, and NHS professionals, working together to improve experiences and outcomes for people following a stroke.

Bruce has documented his experience – from his initial stroke, his treatment, through to his recovery. In a series of three blogs, we will share Bruce’s experience, with the hope that it inspires fellow stroke survivors on their journey to recovery.

Part one: receiving a stroke diagnosis

The day in question

Before I had a stroke, it wasn’t something I had ever considered, and I knew almost nothing about them. I was a fit and active 70 year old, with a fairly healthy diet and lifestyle, although I had been quite exhausted for a week or two before. On the day in question, I had been out in my sailing dinghy for the first time in a couple of months, and I remember it being very tiring to pull the boat out of the water.

Later, as I was preparing a meal with my son, my right leg collapsed under me, and I slid down the wall onto the floor. I was able to stand again after a few minutes, and if it had been up to me, I would have shrugged the whole thing off after a lie down. Fortunately, my son had noticed that the side of my face had dropped and suspected a stroke. He and my wife persuaded me to call NHS 111 and they immediately requested a blue light ambulance to take me to the Leeds General Infirmary (LGI).

When I reached the LGI, I was walking unaided, and I tried unsuccessfully to sleep as I waited to be admitted to a ward. This was back in September 2020, when Covid- 19 regulations were in force across hospitals and the number of cases were rapidly rising, so it was the small hours before I was admitted onto the stroke ward. The next two days were ones I wish I could forget. My abiding memory is of being incredibly tired but unable to sleep. Just as I was finally dropping off, there would be something to disturb me. To begin with, I was just bemused when doctors and nurses came by and asked me to touch my nose – what was the problem? But after 48 hours I had lost the use of my right arm and could no longer stand. On the plus side, I had finally manged to get some sleep.

The doctors told me that I had first experienced a Transient Ischaemic Attack, known as a TIA or ‘mini-stroke’, but this was followed by an ischaemic stroke that had taken out much of the function of my right side.

A TIA and an ischemic stroke share similar causes (a blockage of blood flow to the brain) and symptoms (like sudden weakness, numbness, or difficulty speaking), but the key difference lies in the duration and severity of the symptoms. A TIA causes symptoms to resolve within 24 hours, with most resolving within minutes or hours, while an ischemic stroke causes persistent symptoms and can lead to lasting damage.

My speech was relatively unaffected, although the right side of my mouth felt like I had had injections at the dentist, and my brain seemed to be OK, but my arm and leg were pretty much useless.

In the weeks that followed, I began putting weight on my leg quite quickly, but my arm was much slower to respond and became very painful if I moved in the wrong way.

Coming to terms with my stroke

There was a period of a few days when I went over in my mind why this had happened to me and what could have been done to avoid it. This way of thinking I learnt gets you nowhere and I tried to move on and look ahead to the future. Back at home, my wife had told a number of friends about my stroke, and it was good to get responses and their good wishes. Visiting was very limited because of the pandemic, and soon came to an end completely, but I was able to make video calls home and send messages and emails.

A number of friends did not know how to respond at all to my diagnosis; most were supportive and pleasantly surprised to be getting normal sounding messages, but some people really lifted my spirits. One friend kept up a long running joke about escaping from hospital, complete with sending me in a child’s glider kit, while an old professional friend on the other side of the world found reasons to ask me for advice and stretched my brain to respond. I read a lot in hospital, mostly humorous novels, but I found concentration difficult and the puzzles I used to do in the newspaper were now beyond me. I eventually realised that I had not actually lost brain power, it was just that my brain was working flat out trying to sort out the effects of the stroke and rightly considered that this was more important than playing Sudoku.

Really coming to terms with the stroke took a long time, even though I thought I had accepted the reality of what had happened after a few days. What can you still do and how much will you be dependent on others? It took quite a while for me to sort this out and I have a bunch of things that I asked for as Christmas presents a few months after the stroke which I have still not been able to use.

It is easy to list the things that I can no longer do, but it does mean more time for the things that are left. Reading is actually harder than I thought it would be. For a long time, I couldn’t easily read in bed because I couldn’t put weight on my elbow, and a hardback book needs to be propped up. Writing is fairly straightforward because fortunately I used to be a very slow typist with my right hand, so now the left does nearly as well. Actual handwriting is another matter; I can write left-handed but try to avoid it if possible because it is slow, and the result is not pretty. Apps that transcribe speech into writing are okay but need so much checking that I don’t find them a great help.

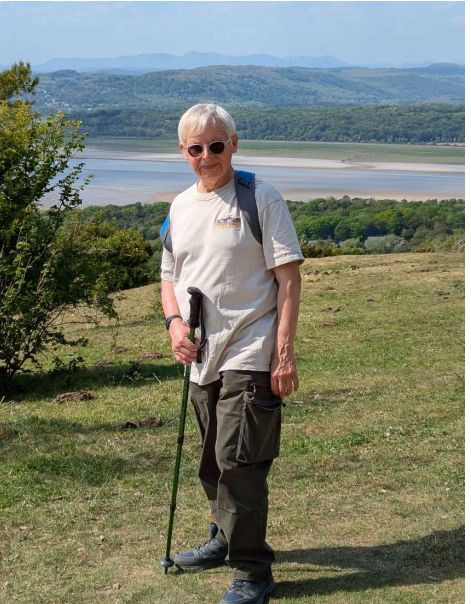

The main thing that I have had to give up on is sailing. I sold my boat pretty soon after the stroke because it was only going to deteriorate and there is no way I can get back to doing all the necessary maintenance, let alone moving around it on a windy day. Less obviously, taking photographs is also a problem. I can manage to use the camera on my phone one-handed, but most real cameras are very hard to use like this, and you certainly can’t take quick shots. It took about four years before I could manage to use an SLR camera again, but the skill is beginning to come back. Something else that was a big loss was hill walking, but again there is now some progress. I always enjoyed the feeling of climbing a hill and being able to see a whole new vista unfold before you. I am now beginning to manage short country walks and even tackle hills; I just have to be very modest in my choice. It is great to start to have that experience again, having initially thought that it might never be possible.

My first outing, a couple of weeks after returning home, to Fairburn Ings. My wife had to wheel me uphill in the wheelchair.

July 2021, with my wife and family having a meal of holiday in Northumberland.

July 2021, with my wife and family having a meal of holiday in Northumberland.